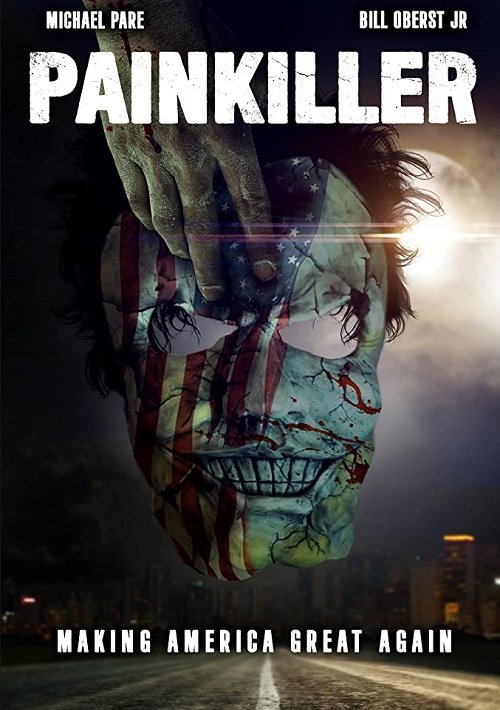

The Personal Take: PAINKILLER (2021)

Author's Disclosure: I'm friends with Mark Savage, the director of Painkiller, so it wouldn't be fair to me to present this piece as a typical unbiased review. Instead, please consider this a essay that reflects on his new film in a personalized manner outside the usual film critique.In my interactions with Mark Savage, the element of his persona that has impressed me most is his comfort in his own skin. He's not interested in playing the games inherent to the film business or trying to repackage his ideas or interests in a way that would ease the risk-averse skittishness of a major studio. Instead, he's figured out a modestly budgeted way to make personalized, distinctive work that speaks to his vision of cinema first and foremost - and to his credit, he's savvy enough to get skilled collaborators on board and create projects that have just enough elements of interest (a hot button subject, a recognizable character actor) that make it possible to get these films distributed. Painkiller is his most recent feature-length work and conceptually it is as close as he gets to conventional filmmaking. The elements of its premise lie squarely in the vigilante genre: Bill Johnson (Bill Oberst Jr.) hosts a talk radio program in which he rails bitterly against the evils of pharmaceutical companies, lambasting them for creating the opioid crisis that claims so many lives across the country while the companies and the doctors who pimp their wares grow richer without legal repercussions. His stake in this is personal: his daughter died from an opioid addiction.But Bill is not content to fight his war with words alone. With secret information from Detective Simone (Khalimah Gaston), he tracks down people involved in the local opioid trade, dons a mask and kills them with a revolver. This puts pressure on pill peddling doctor Alan Rhodes (Michael Pare), a sleazeball who is owned by the opioid manufacturers and is also busy trying to screw an old partner (co-scripter Tom Parnell) out of a valuable patent for the next lucrative pain pill. As Bill and Alan begin to circle each other, they make each other's lives more dangerous in a bloody battle of wills.

Painkiller is his most recent feature-length work and conceptually it is as close as he gets to conventional filmmaking. The elements of its premise lie squarely in the vigilante genre: Bill Johnson (Bill Oberst Jr.) hosts a talk radio program in which he rails bitterly against the evils of pharmaceutical companies, lambasting them for creating the opioid crisis that claims so many lives across the country while the companies and the doctors who pimp their wares grow richer without legal repercussions. His stake in this is personal: his daughter died from an opioid addiction.But Bill is not content to fight his war with words alone. With secret information from Detective Simone (Khalimah Gaston), he tracks down people involved in the local opioid trade, dons a mask and kills them with a revolver. This puts pressure on pill peddling doctor Alan Rhodes (Michael Pare), a sleazeball who is owned by the opioid manufacturers and is also busy trying to screw an old partner (co-scripter Tom Parnell) out of a valuable patent for the next lucrative pain pill. As Bill and Alan begin to circle each other, they make each other's lives more dangerous in a bloody battle of wills. However, Painkiller doesn't play out in the clear-cut manner the above synopsis suggests. The plot recounted above gradually comes into focus piece by piece rather than being laid out in a cause-and-effect manner. There are plenty of bloody shootouts throughout the movie but the film isn't structured around these beats of suspense and action and they don't build up to the kind of shootout/showdown setpiece you might see in the more conventional take on this movie.Instead, Savage and crew mix and match modes, sometimes consciously evoking the style of exploitation films but also presenting moodier, contemplative scenes that evoke arthouse or indie fare. On the former tip, Rhodes is memorably introduced to the viewer accepting oral sex from an addict in exchange for pills and there are some amusingly sleazy tableaus like a dealer and his accompice introduced having joyless sex in a trailer before they're executed. On the latter tip, there are scenes where Bill gives angry but artfully worded monologues to his radio audience, occasionally exchanging observations with them, and scenes devoted to the portrayal of Parnell's character picking up the pieces of his broken life as he attempts to move on.

However, Painkiller doesn't play out in the clear-cut manner the above synopsis suggests. The plot recounted above gradually comes into focus piece by piece rather than being laid out in a cause-and-effect manner. There are plenty of bloody shootouts throughout the movie but the film isn't structured around these beats of suspense and action and they don't build up to the kind of shootout/showdown setpiece you might see in the more conventional take on this movie.Instead, Savage and crew mix and match modes, sometimes consciously evoking the style of exploitation films but also presenting moodier, contemplative scenes that evoke arthouse or indie fare. On the former tip, Rhodes is memorably introduced to the viewer accepting oral sex from an addict in exchange for pills and there are some amusingly sleazy tableaus like a dealer and his accompice introduced having joyless sex in a trailer before they're executed. On the latter tip, there are scenes where Bill gives angry but artfully worded monologues to his radio audience, occasionally exchanging observations with them, and scenes devoted to the portrayal of Parnell's character picking up the pieces of his broken life as he attempts to move on. Anyone who has ever discussed film with Savage knows his tastes run the gamut from the grittiest grindhouse fare to the most aesthetically evolved art films so his mixing of these styles makes sense. He'll be the first to tell you it's all art and it's all worthy of appreciation. His synthesis of these multiple styles isn't calibrated to appeal to all viewers but that's not a bug in the system. It's part of its design, something that makes it uniquely the director's own vision.You don't have to know Savage to appreciate the film's distinctive elements but if you do, it enhances the appreciation. As someone who's spent some time in conversation with him and years observing his commentary via posts on Facebook, here's a few things to note:1) a love for abandoned buildings: a handful of scenes depicting Bill meeting up with his detective contact take place in such a setting and they have a unique atmosphere that backs up the moody quality of these dialogue exchanges.

Anyone who has ever discussed film with Savage knows his tastes run the gamut from the grittiest grindhouse fare to the most aesthetically evolved art films so his mixing of these styles makes sense. He'll be the first to tell you it's all art and it's all worthy of appreciation. His synthesis of these multiple styles isn't calibrated to appeal to all viewers but that's not a bug in the system. It's part of its design, something that makes it uniquely the director's own vision.You don't have to know Savage to appreciate the film's distinctive elements but if you do, it enhances the appreciation. As someone who's spent some time in conversation with him and years observing his commentary via posts on Facebook, here's a few things to note:1) a love for abandoned buildings: a handful of scenes depicting Bill meeting up with his detective contact take place in such a setting and they have a unique atmosphere that backs up the moody quality of these dialogue exchanges. 2) the loving, lush depictions of the outdoors: Mark frequently posts pictures from solitary excursions into nature, capturing the mood of the seaside in the early morning or rural areas that he visits. That aesthetic shines through in establishing shots in this film.3) freedom from conventional morality: a distinctive quality of Mark's work is a refusal to moralize about his protagonists, even when they do things that might be frowned upon by mainstream society. The hero doesn't hesitate to kill in cold blood but does so according to a code, righting the wrongs he sees in an unjust world where the wicked are rewarded as long as they have enough money or power. There are costs for what he does but the film never passes judgment on him. If you sympathize with him, you are free to do so. In a world of audience-tested endings, this is a refreshing quality.

2) the loving, lush depictions of the outdoors: Mark frequently posts pictures from solitary excursions into nature, capturing the mood of the seaside in the early morning or rural areas that he visits. That aesthetic shines through in establishing shots in this film.3) freedom from conventional morality: a distinctive quality of Mark's work is a refusal to moralize about his protagonists, even when they do things that might be frowned upon by mainstream society. The hero doesn't hesitate to kill in cold blood but does so according to a code, righting the wrongs he sees in an unjust world where the wicked are rewarded as long as they have enough money or power. There are costs for what he does but the film never passes judgment on him. If you sympathize with him, you are free to do so. In a world of audience-tested endings, this is a refreshing quality. In summation, Mark's string of recent films continue to impress. They are made on modest budgets but have a professionalism and visual/sonic slickness that rivals things made for four or five times the money. He also casts his leads well: Oberst Jr. brings gravitas to his tormented hero, Pare impresses as an amoral operator who uses self-righteousness as a facade for his scheming and Parnell brings a lived-in hangdog quality to his crucial second-string lead role. The result might not be for all viewers but it succeeds as a personal statement that doesn't pander to audience concerns or commercial trends. That in and of itself is an achievement - and I hope Mark can keep this trend rolling forward.

In summation, Mark's string of recent films continue to impress. They are made on modest budgets but have a professionalism and visual/sonic slickness that rivals things made for four or five times the money. He also casts his leads well: Oberst Jr. brings gravitas to his tormented hero, Pare impresses as an amoral operator who uses self-righteousness as a facade for his scheming and Parnell brings a lived-in hangdog quality to his crucial second-string lead role. The result might not be for all viewers but it succeeds as a personal statement that doesn't pander to audience concerns or commercial trends. That in and of itself is an achievement - and I hope Mark can keep this trend rolling forward.